Olivia Johnston Captures What it is to Exist in the World as a Living, Moving, Breathing Creature

There are some photos that capture more than an image. They evoke an indescribable feeling: a connection to something deeply human or to that which is sacred - or both. Olivia Johnston’s photo-based art captures exactly this strange and beautiful sense of what it means to be a living, breathing, creature, existing on this planet. From her stunning portraiture, to her thematic photo-studies, even to her DJing work, Olivia reaches deep into the minds of her audiences - and brings forward transcendence.

I sat down with Olivia and her adorable dog Laika in her studio on a sunny Friday afternoon, humming with excitement. Through working with the Ottawa Art Gallery, I was already a fan of Olivia’s work; I think it’s hard not to be, with how undeniably human each project of hers is. Looking into the eyes and the souls of her subjects, you can’t help but connect. And the way she explores that humanity, how she holds a mirror up to our understandings of our culture and ourselves, really speaks to the anthropologist in me. I love how she represents reality. I love how she disrupts reality. And most importantly, I love how she shows just how magical reality is.

Read on to hear Olivia’s thoughts on beauty, holiness, and the functions and feelings of art. To quote the artist herself - it’s a cool ride.

AK: Your portrait photography is so incredibly powerful. And portraits are, of course, a big part of your practice. So let’s start there - What draws you most to portraiture?

OJ: I think I've always been interested in depicting people. Being able to represent people who I see in my everyday life, that's always been a part of it. I think one of the big themes in my work is beauty. And this sort of corny idea of everyone being beautiful is something that I really am able to kind of pick up on and represent in my work. It sounds kind of like what a teenage girl would say, but it’s this idea of, I want to show the beauty in everybody.

It's also like, we're all human. So to be able to kind of use humans as a means to explore these questions that I have about the world, and that I have about our communities and that I have about society? I think that really resonates with people.

AK: Teenage girls know a lot, we should listen to them more.

OJ: They know what’s up!

AK: You mentioned beauty there. A lot of your portraiture explores the theme of beauty, but in a way that encourages the audience to question their understanding of beauty. Particularly beauty-through-pain or by challenging beauty standards. What does it mean for you to try and capture beauty in your work?

OJ: I think I’m really interested in beauty because we as people are compelled by beauty. Things that are aesthetically pleasing are like, something that we're naturally drawn to, and there's so much interesting stuff happening there. It's evolutionary biology. There's ideas about gender, there’s so much. There's questions about what it means to try and define beauty. You know? And I think that that is kind of a foundational question in my practice.

Funnily enough, my first successful project, I would say, in art school was exactly this. I wanted to photograph women who I found beautiful. But immediately, I did this project, and then I was like, this isn't enough. We're always looking at images of “beautiful people”. And we're trained to think of straight, cis, white people as the standard for beauty. So how can I go to the other side of that, and push back against it? I could have kind of gone into a more commercial realm, photographing people and making them look beautiful, but immediately I felt kind of troubled by the ability to glamorize the human experience in a way that’s not helpful.

You see this all over social media, this thing of like, ‘oh, this actress, her skin doesn't actually look like that, she's on the cover of a magazine, and it was actually like, Liquify Tool to make her curvaceous in the right way.’ I remember, ten years ago, I made work about this. And I thought like, by now it would be over, but it's actually worse than ever. That's weird to me. So yeah, this relationship that we have with beauty, and with our own beauty and the way we are represented in the world, it's fascinating to me. And I'm hopeful that within my lifetime, we can have a less oppressive understanding of beauty. And we can understand each other as beautiful.

Johnston, Olivia. The Archangel Gabriel (Cara). 2019, Pigment ink print on cotton rag paper.

AK: It’s gotta be hard seeing the medium of photography used to kind of lie about that sort of thing. And so your work ends up being a bit of a challenge to that.

OJ: Totally, yeah. I do kind of rail against calling myself a photographer. Obviously, I'm using photography as my medium. But there are different kinds of photographers, and a lot of the time photographers are working in fields that are used to kind of underscore or like, help the oppressive nature of image making. So to kind of use photography against itself is something that's really interesting to me.

Johnston, Olivia. 15/jeremie (diptych), 2012, pigment ink print on cotton rag paper

Johnston, Olivia. 15/jeremie (diptych), 2012, pigment ink print on cotton rag paper

AK: On that note, I get a sense that you approach some of your projects like a cultural researcher, trying to expose or disrupt something about how our world works. 13-18, for example, really felt like a study of ‘boyhood culture,’ particularly with the photographs of the subjects’ bedrooms. Do you often go into your work with a goal beyond artistic creation - like anthropological discovery?

OJ: I'm interested in anthropology for sure. And I think that like in a past life or a future life, I'll be some kind of cultural researcher. But the interesting thing about art-making for me is that a lot of the time you can create an opportunity for people to sort of pry apart their understanding of the world, in a way that is different from research, different from writing a thesis, or from publishing a book. Because we are these visual creatures, we are compelled by images. Images, period; but images of people in particular. So to use that to catch people, and then try and teach them something about themselves or ask them to question their notions of beauty, of race, of gender, is…it feels like a trick, kind of, but it's like a nice trick. But also, there’s the idea of unpacking even my own responses.

So I think that is a big part of why I make work. Although, you maybe noticed that my early projects were really divided by this kind of thing. Like gender in 13-18. And then in Strength in Disorder, it was women with eating disorders. Whereas with my Saints + Madonnas project, I kind of smashed everyone together. It was like, everyone's magical and holy.

Johnston, Olivia. DL from the series Strength in Disorder, 2011, pigment ink print on cotton rag paper

AK: Yeah - let’s talk about that. In Saints + Madonnas you talk about these questions of holiness that came up for you - like holiness in an agnostic world, or secular holiness. Can you share some of your thoughts on that?

OJ: Yeah, Saints + Madonnas is my most recent body of portraiture work. And I think it really emerged out of a few different things. My art history degree for one - you really encounter so many images of the Madonna in particular, but also just like, the subject of so much of western art history is Christianity. And I haven't actually found that to be explored much within contemporary art. So again there’s this thing of challenging people to think about their expectations about how Jesus looked, about this whole side of visual culture.

But also there’s this idea that has become kind of more prominent within my work more recently, about showing that people are special. And people are magical. And it's actually like a literal miracle that we exist on this planet, you know? That these clumps of molecules come together, and get to exist in this world and experience joy, and love, and empathy, and can play with animals. It's just like…we got a really cool ride, so it’s about bringing people’s attention to that.

Johnston, Olivia. Queen of Heaven (Nneka), 2019, pigment ink print on cotton rag paper, custom-made MDF frame and hand-applied imitation gold leaf

AK: In that vein, a lot of your work references the “sacred” - I noticed that even in the Trauma (Photo Booth) series, where you mention the face as sacred. What does sacred mean to you?

OJ: It’s weird - I wasn't raised religious, and I don't actually feel like I'm that spiritual of a person. Organized religion feels very oppressive to me. But there are ideas around art and religion, and of the practice of making art as meditative, and I think those are foundational, maybe, to how I exist in the world. As people we find happiness in moments of quiet and when the mind is settled, and all these kinds of things.

It sounds weird, but I think mental illness is also part of it. Like how people experience the world in different ways to other people. Or I think of my Mom, who has severely bad vision. And I often think about how it is to exist in the world as her, you know, how she literally sees the world. The idea that we are actually all experiencing a different version of the world, and the idea that the brain is magic, ideas around empathy, all these pieces…I don’t know. It’s a good question. It’s probably the question I’m trying to answer.

AK: The great unknown.

OJ: Yeah, for the rest of my life. [Both laugh]

AK: This might be another bigger question, but since we’re already there - what does it mean for you to try and capture divinity on camera with these projects?

OJ: I think it has to do a bit with setting the stage. When I have people in here, it's dark, the lights on, there’s this setting of the mood, there could almost be candles. So it’s like this experiential thing, where we're both agreeing to put ordinary life on hold for an hour. There's something there that I think is a little bit magic or holy, like in the actual process of making the images. And I also shoot film most of the time, which means that the images can't be seen right away. I think that plays a big role in it too, because people can be affected by their own image.

I had a show in Edmonton recently, and that was the first time many of the subjects saw the photos. [One subject] told me the image really helped them to see themselves in a new way, which is, like, so fucking cool to me. So I think it also says something about our kind of understanding of ourselves and like, our understandings of self representation and the control that we need to have over our own image. Because when I'm looking through my camera, it's like I get to see something that other people don't see. I'm capturing what it is to exist in the world as like a living, moving, breathing creature. And of course the deep irony, or hilarious thing to me, is that I'll never be able to photograph myself the way I photograph other people.

AK: There’s probably something metaphorical to be said about that irony.

OJ: Yeah, I’m doing it for everyone else, but not me, you know... [Both laugh]

AK: Well, do you ever take photos of yourself? In Treasures, you mention how photographs are collected objects, memories. Do you ever take photos for the sake of just collecting the memories?

OJ: It's funny, actually, I was thinking recently about how, like, oh my God, all my memories are on Instagram. And I take tons of iPhone photos. I am interested in that relationship that we have with our phones - you know, like, there's more photos of me on my phone than anywhere else. The Trauma (Photo Booth) series is kind of about that. Before I had my phone, I had my webcam, and I would take a ton of photos of myself, and it ended up being this really interesting documentation of a period of my life. So yeah, I am fascinated by self representation for sure.

Johnston, Olivia. Detail of TRAUMA (photo booth), 2011-2015, 80 chromogenic prints

AK: Does it feel like a different process from taking a photo that you're going to produce for an exhibition?

OJ: Yeah, definitely. It’s been interesting to unpack the difference there - it’s sort of like the difference between being a photographer and an artist. I think we all to some extent have a bit of a collecting fascination with our phone photos. We take photos all the time, more now than ever in human history. It’s this need to have moments of our life, like, collected somewhere and stored away so that they don't go anywhere. But it doesn't feel like hoarding because it's digital, you know I have, like, a shocking number of photos stored in iCloud. And I pay money every month, and like, don't even go back through them. And like, the environmental impact of that? The servers storing all of our images that no one will ever see? I guess it’s something about capturing experience, and just needing to feel tethered to the world.

AK: Trying to capture the magic.

OJ: The holiness. Exactly.

AK: So along with your visual arts practice, you work as a DJ! What got you into DJing?

OJ: It was very random, honestly! And it just sort of keeps happening. I was a classical musician as a child, a cello player. And I’ve always had a relationship with music. But yeah, about seven years ago, my friend Sarah and I started a party in Ottawa. And before that I had told my friend Max I’d always wanted to DJ, and he said, DJ at my next party. So it was really these blessed friends, who were just really supportive and open to me trying out cool new stuff.

So Sarah and I ran this party for a while, and then she moved away. But at that point, I had been involved in enough DJing things that it just sort of keeps happening. It’s sort of an unexpected part of my practice - not really part of my art practice, but part of what makes me who I am.

AK: Do you feel there are connections between your DJing and the themes of your art?

OJ: What we were talking about earlier, about euphoria, and moments of transcendence? Yeah, I think that those are possible to have at like 3:00a.m. on the dance floor. That's what you're doing as a DJ and throwing parties, right? You're creating moments where people are able to kind of have these transcendent moments. And also making Ottawa a cooler place to be. I think that's part of my life mission.

AK: What sorts of things have you been drawing inspiration from lately?

OJ: The idea of human relationships, I think, has been really interesting. It remains to be seen how that will affect my practice. I think there's also a lot of different threads of the Saints + Madonnas work that I'd love to maybe turn into a book at some point. And I've been working on kind of an exploration of chronic illness too, and so there's stuff sort of percolating.

My day job as the Operations Manager at SPAO is like a community arts support practice. That's a big part of who I am. Like, community development, I guess. I would say my DJ work is a facet of that too. So that's more so been my focus the past couple of years. And figuring out how I can remain true to my values while still making work. Mostly life stuff, I guess. But some art stuff too.

AK: The two are pretty intertwined.

OJ: For sure. I'm also not totally convinced that showing art in galleries is the most effective way to get the message across, or how to kind of disseminate your ideas. So I'm thinking more about kind of collaborative experiences - podcasts, you know, these kinds of things. But it’s hard to make all the dreams happen. I’m always excited to see when other people are doing cool stuff though. Pique is really cool. Cool things are happening! So I’m excited.

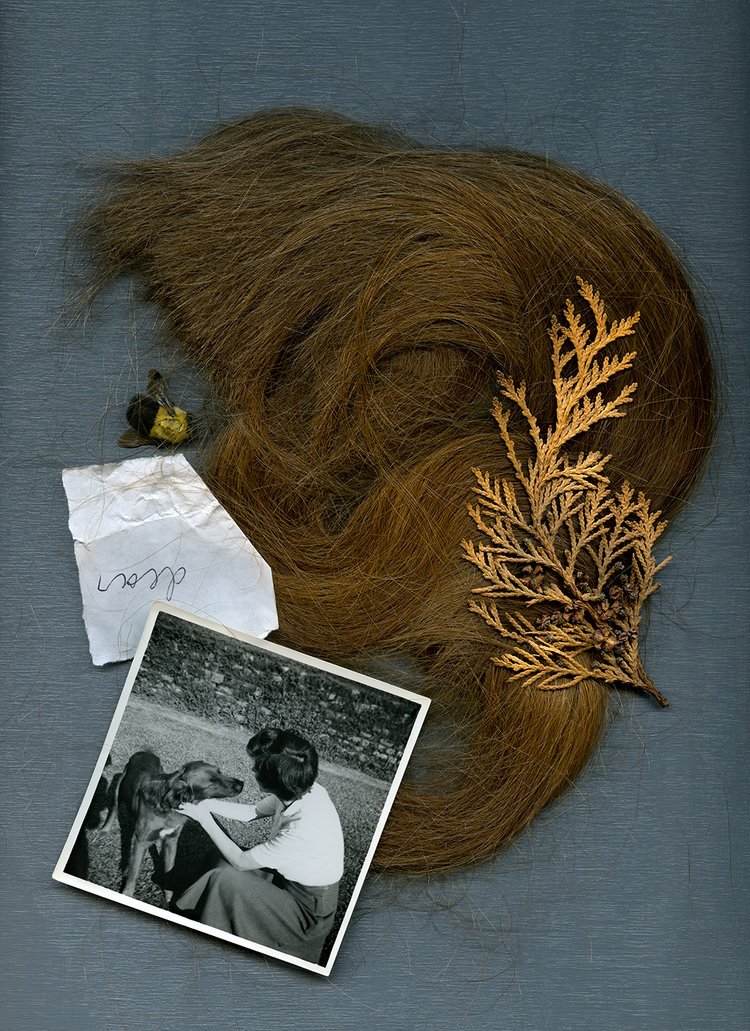

Johnston, Olivia. o dear one from the series Treasures, 2018, pigment ink print on cotton rag paper

***

There was no part of my talk with Olivia that didn’t electrify me. In line with the themes of her work, I had prepared some big questions - pretty much stopping short of directly asking her the meaning of life. But she came back effortlessly with such powerful, inquisitive, funny answers! I ended up with so much to think about. Oh, the joy of new eyes to see the world through. On my walk home, I was so acutely aware of the fact that I am just a clump of molecules, so lucky to be here at all. If bringing attention to that is her goal, then she most certainly succeeded - not only through her art, but simply as a human being.

Our conversation was one of those moments of transcendence. If you’re looking for a similar miracle, I suggest you take a look at more of Olivia’s work, and follow her on social media to keep up with her work and her DJing. Olivia also has a piece for sale in the Ottawa Art Gallery’s Give To Get Art Auction, running Friday May 27th to Sunday May 29th.

Thanks, Olivia.