Radical Acts of Community Care in a Time of Un-Caring

On the evening of February 6, 2025, the Arts Court was a-buzz with the usual energy of a vernissage night, but with a twist – a collision of theatre, music, film and visual art representing over 50 2SLGBTQIA+ artists. The 2025 iteration of Ottawa Fringe’s undercurrents festival included two exhibitions, Pride: Visual Art Exhibit curated by The Ottawa Trans Library and under the q’urrent curated by LuCille Giwa-Amu & Olivia Onuk. The three different venues (Atelier Theatre space, the Courtroom and Arts Court Studio) were packed with nearly 300 attendees; artists (many exhibiting for the first time), friends and family coming out in full support of an event filled with Queer joy and resilience.

In my conversations with curators Wilam (The Ottawa Trans Library) and LuCille (Ottawa Fringe), what was constantly highlighted were concepts that related to radical acts of care, community collaboration, queer archiving, and resistance. According to The Care Collective, “above all, to put care centre stage means recognising and embracing our interdependencies” (2020, p.5) not just through interdisciplinary work in arts and culture, but in how we uplift each other on a daily basis. Whether that is through acknowledging our privileges in a certain space, listening instead of speaking for/over, pairing Elders with the next generation in the same space, or taking a chance on artists who have never exhibited before.

Ottawa Fringe, along with the two exhibitions, was featured at Arts Court from February 6 to February 15, 2025.

Speaking first with Wilam, I asked them how their involvement with Ottawa Fringe began:

Wilam: It’s been over a year now that I’ve been working with Tara who is the founder and head librarian [of The Ottawa Trans Library]. Tara has been just the most wonderful person to work [with] because she really gives me free reign [when] I have an idea. Callie from Capital Pride approached me in the Fall and said it would be really cool to have an art exhibit. She planted the idea, then introduced me to Emma at Ottawa Fringe. We worked together through the undercurrents festival to see how we could bring all of that [Queer, artistic] community together and really make it into an inclusive art event: the theatre and the visual arts.

The seamlessness of this interdisciplinary festival was put on very well. There is this intersection of visual art and theatre. I noticed fibre art costumes, and that made me think of how every day we are performing something – whether it is performing ourselves or performing to conform for safety.

Wilam: That’s interesting. There’s so much performance involved. What stood out in contrast was how crude the pieces were, as if they were stripping away a mask to reveal, ‘This is who I really am.’ It’s nice to have that kind of clear juxtaposition.

When you use the word crude, I see it as a positive attribute as well –

Wilam: Yes! It’s raw.

Exhibition view of Pride: Visual Art Exhibit, featuring pieces by Anthony Campbell and Ehren English. Photography credits: Erik Stoplman (@stoplrightnow).

Folk art includes a sign that someone else in that community sees themselves in. I saw that in the inclusion of craft-associated materials. There were glassworks and collages. Both [types of work] were so respected and elevated in that space that they had this dialogue – there was no elitism [of material].

Wilam: I really have to give that to our volunteers. Art is so influenced by what it’s next to, and so there was this heavy responsibility of ensuring that they were at the right place. I’m so proud of how it came together. There was a lot of soulagement in French. There’s truly that [need] to honour the vision of the artist… they gave their trust [to us] with art pieces that were so vulnerable, and that really needs to be highlighted.

You want to include everything, not censor anyone, but you gave people a choice: signs letting attendees know there were images of undergarments and nudity. You also gave artists the choice of their placements. The whole concept of community agency is being seen in so many layers of this show.

Wilam: Yes, because this is for the community: by the community.

I noticed the works made with the same materials were all separated into different areas. It’s a visual, almost surrealistic, representation of people in conversation with each other.

Wilam: I’m so happy that you got that! Because when we were moving pieces around for those first two nights it was really a conversation of ‘this feels like this wall’ – ‘this feels like the spooky wall’ [both laugh]. But to have so many people [involved] it’s like everybody is dancing with the pieces in a way. It was truly a collaborative process from the beginning to the end.

And when you did this initial call, did you have a theme in mind?

Wilam: There was no theme. With the Queer community, it’s a patchwork of everything. Part of being Queer is also not wanting to be limited to anything. I think that’s a really strong feeling. We couldn’t have planned for this diversity of materials and themes – and yet, that’s the beauty of the Queer community. It all flows together naturally, expansive and all-encompassing, as if it created itself.

The show itself was an embodiment of the works, in the way that it was very DIY – it came together [the process], and came together [the final show, the people].

There was a playfulness to the show – so much life and colour, that in spite of everything, there is joy. It was very emotional actually.

Wilam: And that’s the beauty of art, it really was an expression of the pain, the joy, and then the hope. That’s why I think nobody left too heavy. It was just real…people showing their true selves and that journey they’ve gone through and the celebration. All of that balanced one another.

It’s like radical acts of care. If everything else fails, we don’t fail each other.

Thinking about The Ottawa Trans Library, I think of archives. This show is very much a visual archive of the existence of community care.

Wilam: It is a visual archive – I think there can be so much censorship but art will always exist. You can’t stop us from creating art. Art is so powerful – that’s how I get through this. There’s something almost rebellious about it because the more they try to censor us – through erasure, through suppression – the more determined I am. I’ve created more [now] than I’ve created in a long time. Other artists are feeling the same. It’s about counterbalancing what’s being erased. We don’t give up a fight.

Acknowledging privilege, some artists are perhaps used to deciding where and how their works are exhibited. But there were first time artists who were just happy to be there, showing that there are still barriers in the art world that we, knowingly or unknowingly, create/uphold.

Wilam: Tremendous barriers, especially for the Queer community. Many in the Queer community live under the minimum wage, and don’t benefit from family support – we create our own families. Art is an accessible way of expressing yourself and that’s why you saw so many different mediums used; it’s what you have access to.

I’m proud of everybody who came together for this, I’m so grateful to so many people who kept messaging me, asking what we needed.

As we continued our conversation, Wilam remembered an important story, which highlighted the importance of this art exhibit.

Wilam: We received an email from a father who came with their son to the exhibit. Later that evening the son turned to them and told them that they were trans. You realize how [representation] truly is lifesaving, it really is. You do it for moments like that. You showed them that despite all the negativity surrounding being trans, there is so much beauty. We have it, we live it – this vibrant, beautiful life.

Visibility is lifesaving, it really is. When you can see yourself, then you give yourself the right to be. There are so many opportunities for meaningful conversations [between parents/kids].

Thank you for creating another important event for the community. It is nice to know that despite it all, there are still these spaces, and more people are feeling safer, braver to be who they are.

Wilam: Braver for sure. And the more we are in numbers, the more we can be in public spaces. LuCille was the curator for the Atelier; it really needs to be covered. It included three trans, Black individuals and the room was packed with community.

I think there needs to continue to be dedicated spaces like what LuCille did, because we can continue to grow and learn together. We’re going to have to continue to ensure that we’re enabling those activities – that is not something we can do on our own. LuCille truly honoured what their community needed in the moment; creating a special energy of family. We need to continue to make space and keep dialogues open. LuCille’s exhibit spoke to the community differently. For those who saw themselves in the show, it was like breathing: ‘finally’.

Talking with LuCille, I asked them how they had planned out the show – what was the process, were there any themes?

LuCille: under the q’urrent was a little bit more specific because it was for LGBTBIPOC, specifically Black, trans artists. Whilst it was a closed practice/space in a sense, it was also a united experience: it was open to be seen and experienced by others.

Undercurrents are waves that guide the tides, but are not immediately recognized. Applying that with Black, Queer, trans people, it’s how we have shaped society without gaining that recognition. Pieces that wouldn’t be recognized by galleries, got a chance to [be recognized]. There’s this entire idea of Black excellence, and as much as I love Black excellence, I think it can be limiting, because what is excellence? Why can’t people just show up how they are? My idea with curating that exhibit [comes from the artists] being multi-disciplinary and raw. The centrepiece quite literally is a work on an unstretched canvas suspended in the air.

Could you speak more on the talkback portion of the event?

LuCille: I asked a series of questions about the artist’s craft, what their obstacles are, whom they do this for and why they won’t stop. An obstacle that one of the artists mentioned is that their art rarely gets accepted into galleries. It’s not what people call ‘well done’ art. There is a level of colonial thinking that comes with art institutions here in Canada. My entire idea with the exhibit was that I wanted artists to come and do their [own] thing. Gothbitch calls themselves an expression artist: they paint, they create mixed media art, but they’re also a DJ and they host pay-what-you-can events. Aly is a painter but they [also] instruct bigger groups [in the community]. Starr Carter is an up-and-coming filmmaker and their piece was [about] the ballroom kiki scene. The organization Touch Grass let Starr sit in on one of their practices; they got a bunch of film from just that.

Could you speak about the intentions of lighting in the Atelier?

LuCille: The lighting plays a key role in that feeling of being underwater. It is just an added extra je ne sais quoi if you will. You also get to put on headphones and listen to the video, and just see what that community is like in action. During the talkback we also had a coordinator from the collective [Touch Grass] sit in and talk more about ballroom and what that does for Queer and trans people in the city.

I liked that it was connected with Fringe - there often is too much disconnection even within the arts but all disciplines are interconnected.

LuCille: The arts are under attack. We all need to come together; we cannot be thinking that we are one body. We need the arts; yes we need doctors and engineers, but we need artists. We need artists to document, to keep us alive, to encourage the masses, to motivate people, to make people feel seen. I’m so passionate about this topic, especially because I am multidisciplinary myself: I am a painter, I’m also a tattooer, I’m also a filmmaker, I’m also a theatre director. We’re in a time where we need a coalition. And I feel like that is what the undercurrents festival did.

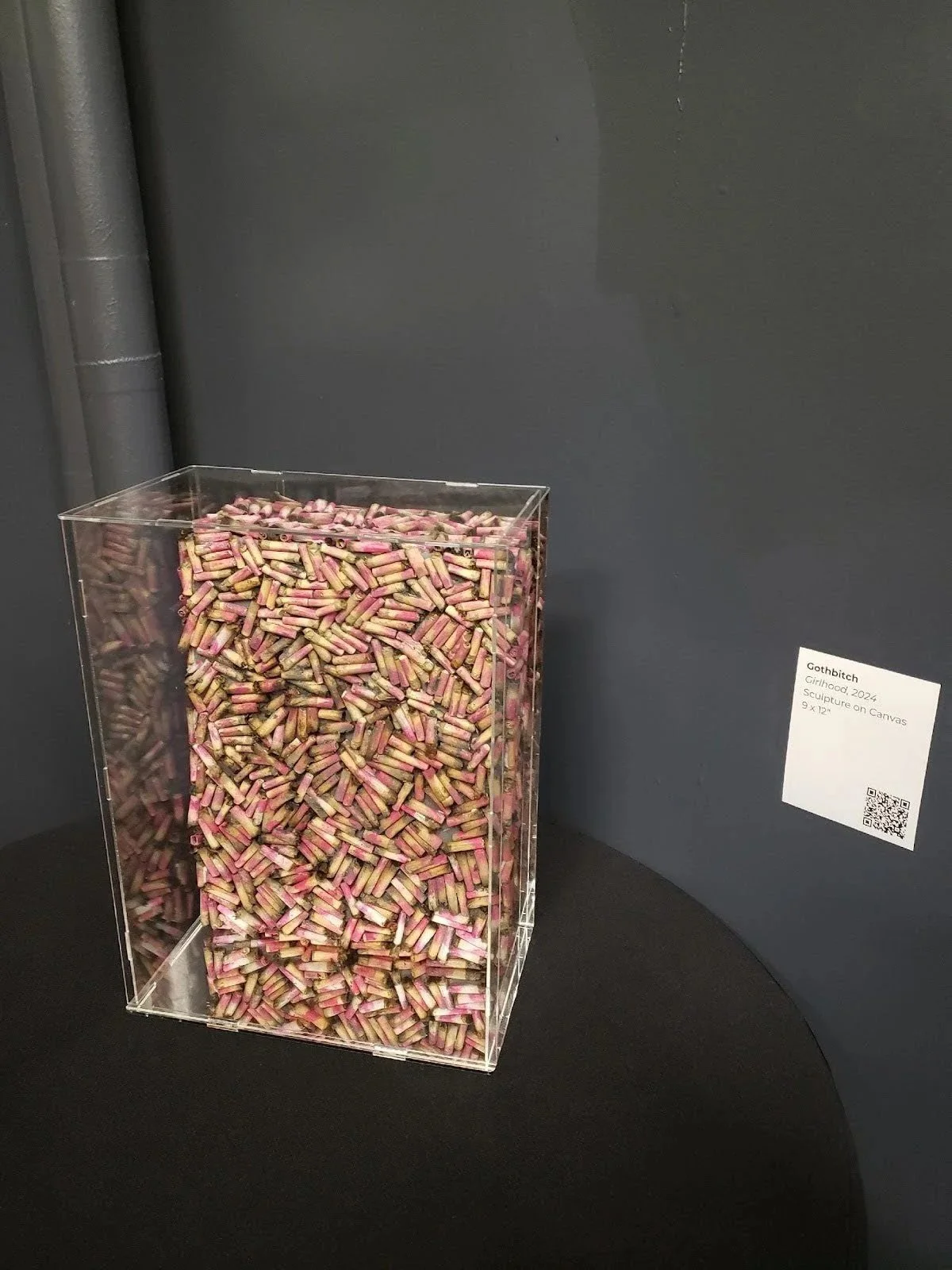

Gothbitch. Girlhood. 2024, Sculpture on Canvas.

Thinking about the work being raw, that was something that I noticed throughout the show. Immediately in my head I was thinking ‘this could be folk art’. This is craft, this is a community symbol, and it represents a community.

LuCille: That piece [Girlhood] is by Gothbitch and they actually went around asking their friends [for their joints]. So even some of my joints are in there. It’s quite literally a piece about community coping. Because they got that from friends, and friends of friends of friends of friends, trying to cope.

It’s like a twenty-first century community quilt – it has a whole other aura to it knowing now that it was collaborative.

LuCille: Exactly! That’s very powerful because when you look at that, not one person can smoke it, because not one person did smoke all that, you know?

When you were thinking of the show, was there a call out or did you know the artists’ work beforehand?

LuCille: I wanted artists that interact with their community in a substantial [way]: artistic leaders. These are all people at different levels in their career. Aly is further out in their career, while Starr is really just beginning. They all have taken up space at their various levels of work. It was really important for me to have Starr because they are documenting things as they are happening in time. These videos that they take now, when ballroom ends up becoming a bigger scene in the city, are going to be pulled from the archives. Gothbitch is a Nigerian, Queer, trans DJ that is actively hell-bent on making events accessible. It’s not just what you do in your private practice, but what you do in your public practice as well.

The generations are in solidarity with each other: youth and Elders. And when I say Elders I don’t mean that the people there are old, but they are the Elders of the next generation.

LuCille: When we think about Queer Elders, historically, they are not typically old. Unfortunately, a lot of Queer people die early: think about the AIDS epidemic. The term Queer Elder is a very subjective term. You can be a Queer Elder and be thirty-five. It just depends on your tenure in the community. It is about how long you have worked in that community.

Creating this documentation is very important. Even the show itself acts as an archive overall.

LuCille: I have yet to even fully process it. Just hearing from Starr on their Instagram, they posted about how it was such a life changing opportunity for them. I think it’s very interesting when you work in arts administration because you are constantly [working] to give artists a voice. By the time people tell you how amazing it is, it can be a little hard to process.

At the opening I could hear all these separate voices of artists exclaiming ‘that’s me!’ Everyone was so happy. To see so much joy in one space was moving.

LuCille: That night we had both vernissages, but we also had a theatre production, En Sortant de Cochrane [by Alain Lauzon], which was a Queer story, and that show was also sold out. It was such a beautiful day of celebration. The place was packed from corner to corner. The people that were there…were there to feel seen.

Could you talk more about the choices made [re: production]?

LuCille: I curated this exhibit in hand with my mentor, Olivia Onuk. It was very important for us to make sure that the pieces were all elevated. On exhibition day, we had Starr’s video playing and a projection screen with a short film from Gothbitch as well. Gothbitch was spinning tracks, framed by a mirror and their work. Aly’s work was all over the front space. I actually have the lighting tech to really thank – Garret Brink, who designed the [underwater] lighting, Ted Forbes who also helped, and tech assistant Glen. I will say it was very much a team effort.

Exhibition view of pieces by Aly Joy-Lily McDonald in under the q’urrent.

Two very different exhibitions yet intertwined in similar struggles of representation, acceptance, community building and family making; of kinship building. The idea of kinship, reminds me of The Care Collective’s thoughts on caring about kin across difference: “the more challenging issue when it comes to imagining new models of care is that of caring across difference - whichever way ‘difference’ is constructed in a particular time and space” (2020, p. 38). The artists do not just highlight differences (read: unique identities) in the exhibits, but create webs of connections that unite the Queer community. The artists participate in a remixing and rearranging of representation, and this act “is about finding ways to innovate with what's been given, creating something new from something already there." (Russell, 2020, 134).

Learn more about Fringe and the undercurrents festival here: https://ottawafringe.com/undercurrents/

And, The Ottawa Trans Library: https://ottawatranslibrary.ca/

Works Cited:

Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. Verso Books, 2020.

The Care Collective. The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence. Verso Books, 2020.